7 South American Films About Justice

7. Heroic Losers (La Odisea de los Giles, 2019)

Ricardo Darín and his peers in Heroic Losers.

A Hollywood flick in Argentina. A bunch of average losers band together to get their money back from a corrupt capitalist. Portraying rural, economically depressed areas of Argentina with its colorful types, the film bets high on humanist ideology – a brotherhood of the downtrodden: only that could stand up to the rich and powerful. If only we could get together, work together, then…. So on and so forth.

The film’s not a comedy, but it relies on the ineptitude of its heroes; the film’s not a political drama, though it relies on its populist politics. It ends up being neither here nor there, stuck midway in its route to being an excellent film. But it's good enough, since it’s often light and unpretentious.

The explicit moralism towards the end and the cringy mellowness almost ruin it. But they don’t, at least for those who enjoy a happy ending, which might be a flaw in character. That’s the film’s target audience: those who want to rest, feel good, and get slightly political, just enough to avoid angst and serious thought after a hard day’s work.

6. Elite Squad (Tropa de Elite, 2007)

BOPE officers in a Rio favela: SS tactics against drug gangs.

Fascism Brazilian-style. A cult classic in Brazil due to its outstanding script which coined not one or two, but a whole bunch of neologisms and slangs in Brazil’s ordinary language. And yet Elite Squad is, at its core, morally rotten.

A certain paramilitary ethic (and aesthetic) dominates the film. The police officers working in Rio’s BOPE (an elite unit) dress in black attire, their symbol is a skull, and their methods are not unlike those of a military dictatorship: torture, general disregard for privacy and rule of law, and sheer vengeful homicide disguised as justice. These types are portrayed as heroes since they don’t take bribes; the drug dealers are the nasty villains, and the pot-smoking students are the silly bourgeois left wingers who in their hypocrisy and depravity finance crime. But given how BOPE goes about its business, corrupt cops don’t seem all that bad.

And yet, despite being an ode to police violence, the film is often considered a comedy of sorts, with a typically Brazilian taste for bawdiness, informality, and laughter in the face of poverty and widespread corruption. Morally ugly and quite a lot of fun. Only in Rio.

5. Carancho (Carancho, 2010)

Ricardo Darín, the Argentine common man, and Martina Gusmán in Carancho.

A tense thriller of hospitals, shabby apartments, and ruined lives. Everything starts and ends in a car accident. At first, it feels like romance; then it descends into penal code territory: extortion, fraud, drugs, murder. And car accidents.

Morbidness pervades the Argentine urban landscape. We have a rascal (Ricardo Darín) hoping for a last shot at redemption; a depressed, addicted doctor (Martina Gusmán), her life a constant infirmity. Such a match, which could feel accidental (the film’s favorite metaphor) or made in hell, is so naturally acted and scripted that it feels like a necessity: a sort of necessary accident. The only thing certain is that accidents decide life and nothing else.

With a courageous ending which makes up for some of the sins in the narrative, Carancho is a sort of contemporary Argentine noir, fatal and utterly derisive of free choices.

4. The Man Who Copied (O Homem que Copiava¸ 2003)

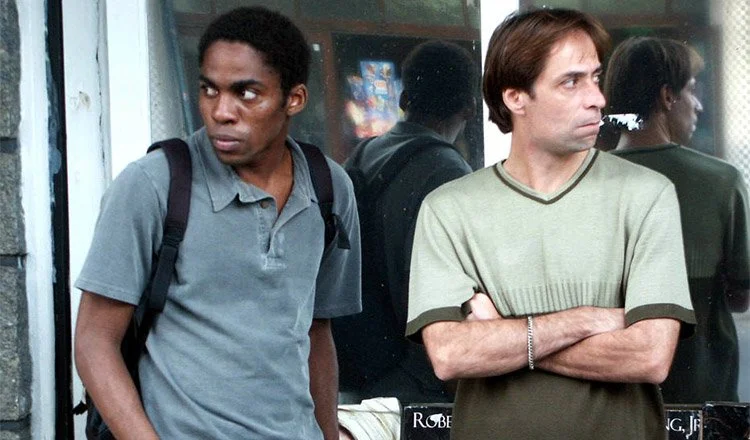

Lázaro Ramos and Pedro Cardoso in The Man Who Copied.

A fine example of contemporary Brazilian realism in cinema. The Man Who Copied, though a bit irritating when it loses itself in video clip aesthetics and animations, is an efficient tale of moral decline, from money counterfeit to parricide. And, of course, being a Brazilian film, the whole thing is comical.

The cast is perfect: Lázaro Ramos, as a black young man, as poor as they come in Brazil, who just can’t seem to get ahead; Luana Piovani, a knockout, as material girl dreaming of a black Mercedes; and Pedro Cardoso, who steals the show as a down-and-out loser that, above all, looks like a loser, even when driving a Mercedes, which he buys in the wrong color.

The film has some Nouvelle Vague levity to it, but with less emphasis on references to American films and more on Brazilians’ general malaise: lack of dough. The main character is broke, so broke he can’t even put his hands on a 50 reais bill (roughly 10 dollars) in order to counterfeit it. “If I had 50 reais, then I wouldn’t need to counterfeit it…”, goes his logic. From such harsh reality, it doesn’t take much to stretch the limits of moral action. It’s enough to make The Man Who Copied a quintessential Brazilian story.

3. City of God (Cidade de Deus, 2002)

The way of the world in City of God.

Justice gangsta-style–– in the Brazilian favelas. The virtues of Fernando Meirelles’ City of God (2002) is the brutal immanence of moral equilibrium: there is no transcendent, external force which can bring moral balance to this bloody tale of psychopathy and power struggle.

In City of God everything is decided within the very structure which gave rise to violence in the first place: no police, no law, no fate – like God, this favela, City of God, takes care of everything by itself, it is entirely self-sufficient, and constantly self-recycles in blood. The kids who were bullied kill their elders and take their place as sadistic drug dealers, and then… get killed by the kids they bullied which take their place as sadistic drug dealers. There’s no end to it.

City of God feels like a mythological story because the social problems it tackles also feel like this in real life: as ahistorical, myth-like patterns of endless violence. We see no way out of it (the brutal inequality which allows for misery and violence in excess) and thus City of God hits home.

2. I’m Still Here (Ainda Estou Aqui, 2024)

Fernanda Torres in Oscar-winning I’m Still Here (2024)

Modern political experiences in South America concern mostly one thing, namely, the struggle for democracy, so very young and fragile in the continent (as it is everywhere else).

Walter Salles’ I’m Still Here (2024), a true story, taken to dramatic heights by lead actress Fernanda Torres, concerns the quotidian experience of political oppression, and moral action against it, during the Brazilian military dictatorship (1964-1984) which severed the social expectations of a generation.

Eunice Paiva’s husband, a dissident politician, disappears. His absence becomes the substance of lifelong political engagement tangled up in grief: when the boundaries of public and private life are disrupted by State violence, then it becomes necessary for personal affections and memories to turn into political weapons.

1. The Secret in their Eyes (El secreto de sus ojos, 2009)

Ricardo Darín again, now in Juan José Campanella’s masterpiece The Secret in Their Eyes (2009).

A modern classic, The Secret in their Eyes is many things: a love story across decades of political upheaval in Argentina, a moral drama of crime and punishment, an exercise on memory and meaning, and an ode to everyday Argentine-ness, with name-callings (“Pelotudo!”), government corruption, local bars and cantinas, public buildings and criminal justice bureaucracy. And, of course, football: the one-shot sequence at Huracán’s stadium might be one of the greatest of all time and remains apparently impossible. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wE2gTZN-oPU)

Ricardo Darín, Argentina’s James Stewart, delivers his best performance as a second-rate law officer in the Ministerio Público (D.A.), caught up in the toils of a murder investigation which ends up revealing much more than a culprit. The violence of a country’s political history, as in Doctor Zhivago, determines the lives of the characters, and the past is insistent to the point of impeding the future, as in a film noir.

The ending should not be read as happy, but as inconclusive. There’s no possible happy ending after what happened – and quite a lot happened during Argentina’s military dictatorship, which left no lives untouched.